On handwriting beyond learning; as art and spiritual praxis

When is handwriting just scribbling something down and when is it something sacred? East Asian cultures uniquely elevate writing beyond communication to a profound artistic expression, a discipline and a way of life. While not my native language, Japanese calligraphy served as my introduction to visual writing arts, which i subsequently followed up with further studying into European calligraphic traditions. This of course exists entirely distinct from my creative writing practice, which operates on a different conceptual plane.

In Japanese there are two translations and corresponding characters for calligraphy. These two concepts frame the understanding of calligraphy. "Shuji" combines the characters for "learning" (Shu) and "characters" (Ji) appropriately translated as "penmanship." This represents the foundational relationship between the individual and written language, the systematic approach through which one first masters the mechanics of writing. It is methodical, precise, and governed by clear standards of execution.

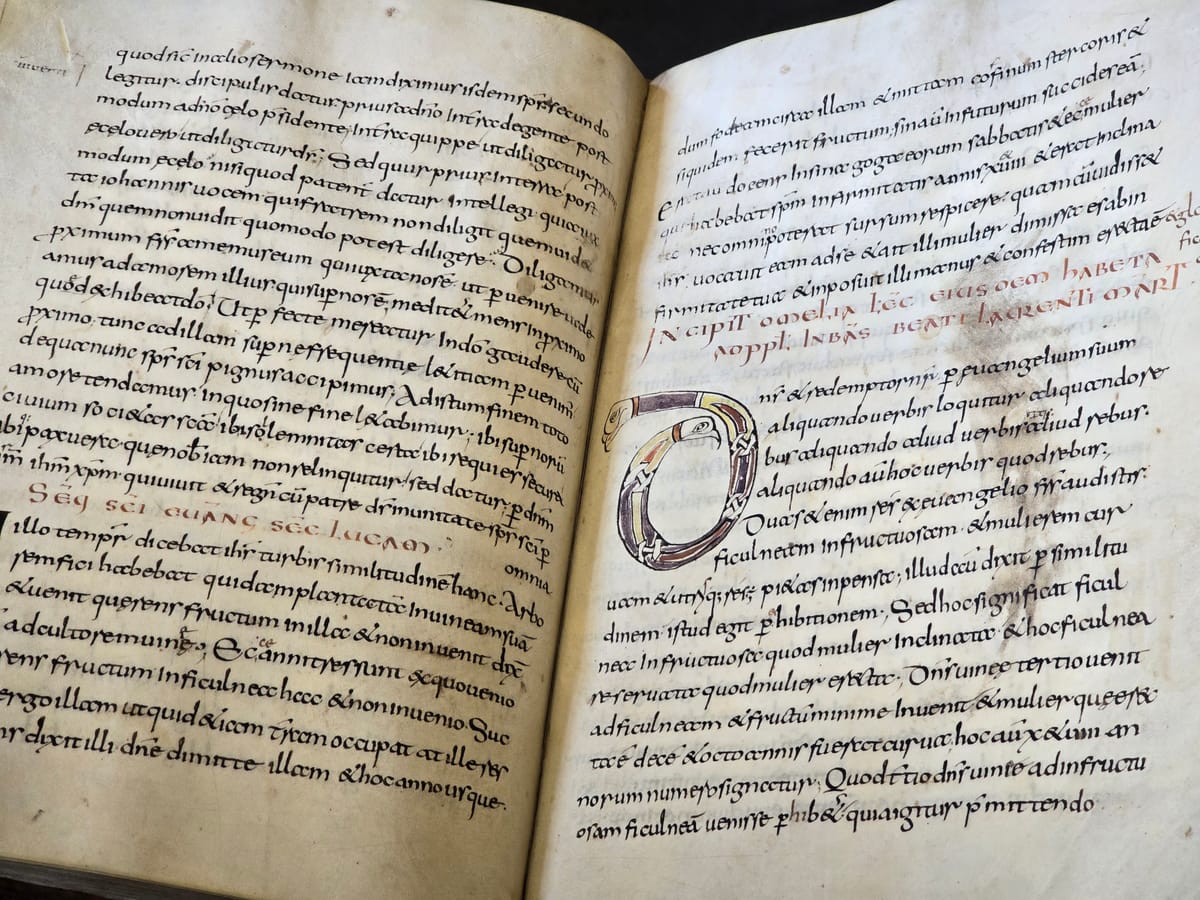

In contrast, "Shodo" merges "writing" (Sho) with "way" (Do) to create a meaning slightly different from just "calligraphy". More like - "the way of writing." This distinction is crucial. The character "Do" appears consistently throughout Japanese artistic traditions - in "Sado" (the tea ceremony), "Kado" (flower arrangement), and martial arts like "Judo." This is no linguistic coincidence but rather a philosophical framework that elevates certain practices beyond technique into comprehensive spiritual disciplines. In other words, this isn’t just a skill, it’s a path to something greater. Soon after taking up Japanese calligraphy, i began studying Western calligraphic traditions: Modern Copperplate, Spencerian, Gothic - yet i couldn’t identify a similar tradition. Of course many of these scripts were originally practiced almost exclusively by religious patrons, the writing served to transcribe the word of god, yet this tradition did not carry over to the common folk and certainly didn’t become widespread in the same way East Asian calligraphy is so ubiquitously practiced. While it is generally acknowledged and, to some extent, desirable, to retain a distinct sense of individuality in these scripts - we trained rigorously to achieve balance, conformity, and harmony that often sought to align our writing with established references. Similarly, handwriting when arriving in the form of personal invitations, letters and the like - might be cherished by recipients but they do not carry the same spiritual weight found in East Asian calligraphy practices.

It is worth segueing here to say that i cannot express enough the importance of handwriting in every day life. It is not a quaint, analog hobby for people who can’t handle technology (my film photography, arguably is, though you’d have to pry that from my corpse). Handwriting is divine. Every creative breakthrough, every achievement in my education (Harvard referencing essays before AI existed), every piece of information i have been able to retain in this distracted hellscape of modern life - i can trace back to my irritatingly obsessive habit of writing things down. The magic that happens between the brain and the hand when writing something down, it cannot be replicated by typing. In creative writing the ideas that flow from pen and paper is unmatched. Understanding writing as an embodied experience will unlock an internal force that can only be understood through doing. The practice of writing i do for artistic merit is just a bonus. Back to the subject…

"Shuji" represents disciplined conformity - balanced characters, even strokes, and consistent sizing taught in primary education. It builds competence through adherence to structure. It’s like a bootcamp for your hand.

"Shodo" however, transcends these boundaries. It is artistic expression in its purest form, where the calligrapher moves beyond technical perfection toward personal truth. The practitioner of Shodo does not pursue uniformity but rather authenticity - allowing individual character to emerge through the relationship between brush, ink, and paper. It becomes a dialogue not a monologue.

This distinction between "Shuji" and "Shodo" offers insight into a philosophy that mastery begins with discipline but culminates in transcendence. The journey from technical proficiency to artistic freedom reflects not just an aesthetic philosophy but a comprehensive approach to knowledge, self-development, and ultimately, enlightenment. In this way, the simple act of forming characters becomes a vehicle for spiritual growth - a practice that engages body, mind, and spirit in the pursuit of beauty and truth.

Anecdotally, i recently discussed the spiritual practice of calligraphy with a gentleman from Beijing who was horrified to learn of Japanese practitioners using a grading system for calligraphy stating that something so internal, so subjective and individual could never truly be graded. Which is true of many things in this life.

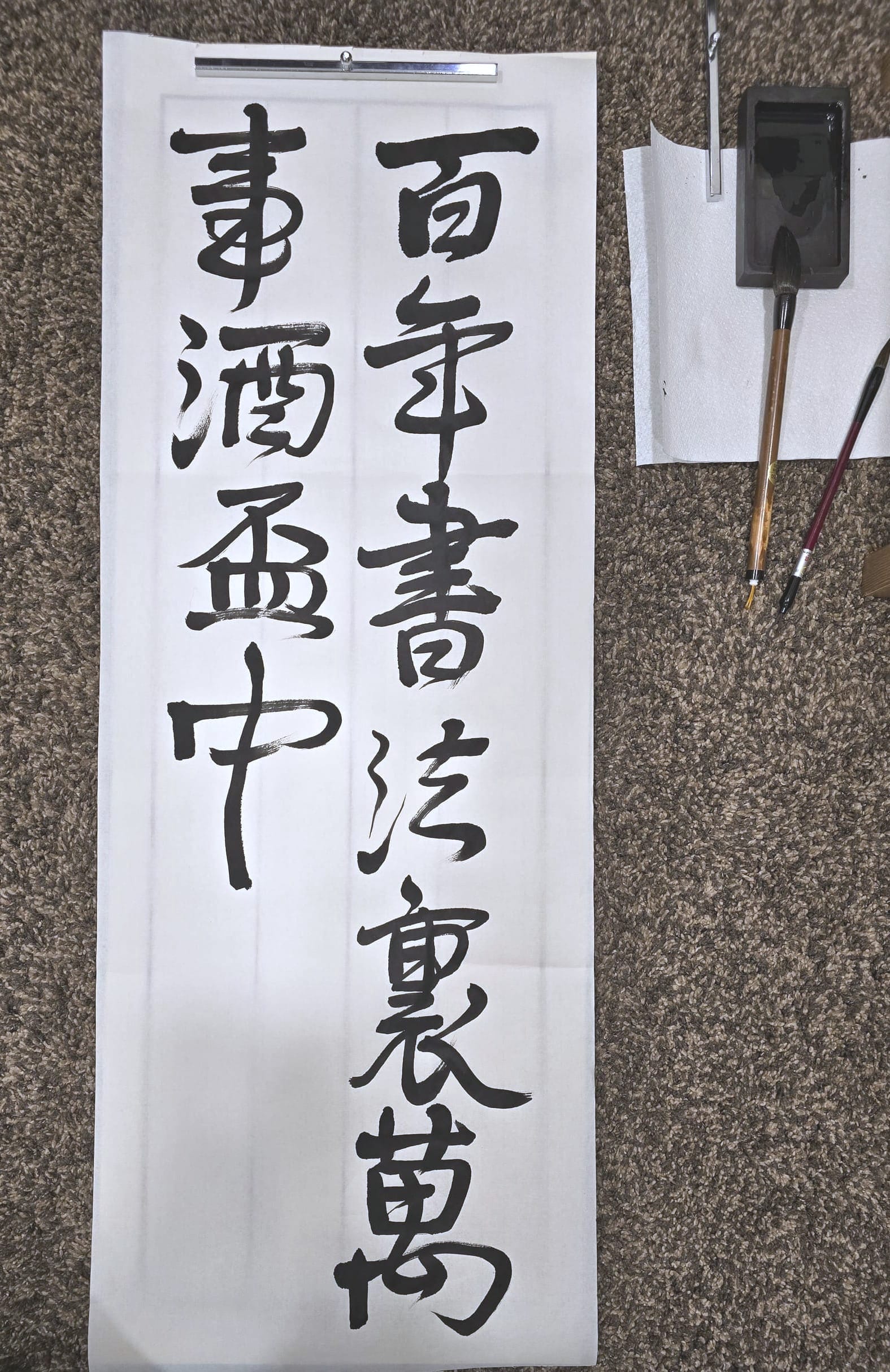

New Year 2025 competition Shodo artwork - 100 year of calligraphy

{Reading: I will spend my whole life discussing calligraphy. I will throw the things of this world into a cup of sake}